On Jan. 11, 2016, very early in the morning, with the Christmas decorations still up, when I was still living in Milpitas, Calif., I was shocked to see multiple sources reporting the death of David Bowie at age 69 during a period marked by the deaths of several aging rock stars, including Lemmy, Glenn Frey, Paul Kantner, and Keith Emerson as well. I had lost track of Bowie’s career sometime in the early 2000s, so I simply assumed he and Iman were living in New York and London, being beautiful, wealthy superstars together. Needless to say, Bowie hid his cancer diagnosis remarkably well from the media until his demise.

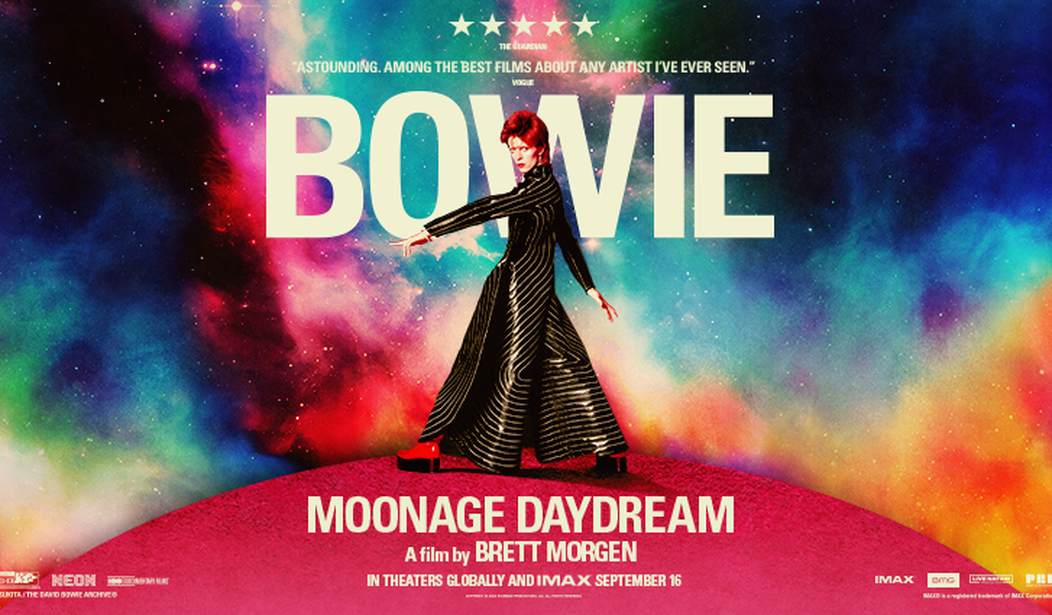

In the years since his death, Bowie’s family gave director Brett Morgen a massive archive of material to assemble Moonage Daydream, which played briefly in theaters in September before being released on Blu-Ray in November. I saw Moonage Daydream in Fort Worth on Saturday, Sept. 24. The soundtrack, while deafening (I almost wish I had brought the earplugs I wear these days at rock concerts), made great use of surround sound.

Bowie was an unusually multifaceted artist: songwriter, singer, sex symbol, actor, and a surprisingly talented expressionist painter. He was both a hitmaker as a musician and wildly experimental. His 1970s use of characters to hide behind (Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke), and outrageously disparate artistic phases (his “plastic soul” and Berlin era) would directly inspire Madonna in the 1980s and 1990s. Numerous MTV stars, such as Duran Duran and the Psychedelic Furs, would borrow heavily from elements of Bowie’s ‘70s style.

In an interview with Guitar World’s Brad Tolinski, Jimmy Page stressed the importance of England’s art school system on British bands of the 1960s. “Remember, just about any British band that came out of the sixties worth its salt had a least one member that went to art college, which was a very important part of the overall equation. It wasn’t unusual at that time to be interested in comparative religions and magick. And that’s it. It was quite a major part of my formative experience as much as anything else.”

While Bowie didn’t attend art school, he spent three years at Bromley Technical High School being taught by Peter Frampton’s father. In his 2020 autobiography, Frampton wrote, “My father’s passion was teaching art. He could see those students who had the eye and the excitement to learn when they walked into his classroom. Dave Jones was one of those.”

Laser Bowie

In his 1983 history of The Who, Before I Get Old, rock critic Dave Marsh described the band’s classic 1978 documentary, The Kids Are Alright:

Kids is one of the most anarchic documentaries ever assembled, running two hours without a shred of narration and with not so much as a subtitle identifying characters or dates. Kids was the perfect cult item and Who fans flocked to it. Hardly anyone else did, however, so it remained a staple on the midnight movie circuit, part of every kid’s introduction to the verities of the Rock of Ages, the film had little impact outside the Who’s cult. The Kids Are Alright is, nevertheless, one of the great rock & roll movies, capturing all of the Who’s sass and humor and taking the wind out of the bands pomposities at each and every opportunity.

But The Kids Are Alright was a transparent and linear documentary compared with Moonage Daydream — and a documentary with a sense of humor, also something mostly lacking in Morgan’s film. The final product is a strange mess of a film. As Slate’s Carl Wilson notes in his review, Morgen tried to create not so much a documentary, but a cross between the “Laser Floyd” and “Laser Zeppelin” shows that planetariums show on weekends, and an amusement park ride:

This isn’t just me being snarky. Morgen himself told the Los Angeles Times last week that his two most crucial influences here are “the Pink Floyd Laserium at Griffith Observatory” and Disneyland. “I like thinking of my movies as theme park rides.”

And hey, what don’t you get from a rollercoaster that you might want from a documentary? Just little things like any sense of context or chronology, the identification of key figures, et cetera. I don’t mind that the narration is all excerpts of Bowie interviews. As one of the most erudite and eloquent rock stars ever, Bowie has no need of the rote talking heads in most music docs. But he also famously switched his stories and ideological lines frequently over the years, and it’s vital to interpreting him to know when the quotes come from. But this director is actively opposed to even on-screen captions. As Morgen told the LA Times, “I was trying to create an experience, and what’s the opposite of an experience? I would argue it’s information.”

That stance strikes me as not only (unintentionally) quasi-Trumpian but squarely hostile to Bowie as an artist. Yes, he generated mystique and contradiction, but he did so at the place where experience and information meet, every album laced with backstory and further signposts to artistic, cultural, philosophical, and sociological inspirations. What he loved was information overload. He was never anti-intellectual, except during the mid-1980s Let’s Dance phase when—newly recovered from years of drug addiction, broke, without a record contract, and usurped by a new generation that recycled all his past ideas (none of which you’d know from Morgen’s movie)—he conveniently decided the one style he’d never tried was mainstream pop.

In between concert footage, there’s repeated footage of Bowie in what the kids call these days “liminal spaces:” scenes of early ‘80s-era Bowie walking through malls and riding escalators which are repeated multiple times throughout the film.

However, the film does give a sense of Bowie’s headspace during the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. The ‘70s footage includes some great concert footage, brief clips of Kenneth Anger’s art films, and scenes of Bowie appearing in his first film, 1976’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, directed by Nicolas Roeg. There are clips of Bowie being interviewed by Dick Cavett, where a twitching plastic soul-era Bowie looks quite stoned. In order to clean up, Bowie moved to Berlin, where he produced a trio of experimental albums with King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, former Roxy Music keyboardist Brian Eno, and his frequent producer Tony Visconti.

Morgen has numerous voiceovers of Bowie discussing how much he hated the clean-cut pop of much of his 1980s music, and while this is true, it’s somewhat deceptive, as Slate’s Carl Wilson notes:

Moonage Daydream includes some fascinating quotes in which Bowie seems to repudiate that whole [1980s] phase as “the vacuum of my life.” But I would bet their placement is misleading: He often said he regretted the couple of throwaway albums after the mass success of Let’s Dance, but he never disowned the excellent hit album he’d made with Chic (and later Daft Punk) studio mastermind Nile Rodgers, who by the way is never mentioned in this film. Morgen also accompanies his segment on this period with a flashback to an early 1970s Ziggy Stardust-era concert performance of “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide,” converting Bowie’s own song into preachy ammunition against its maker.

With the exception of Robert Fripp and Brian Eno contributing during his Berlin phase, there’s little talk of the many sidemen Bowie used to shape his sound. While a great singer, Bowie was not the equivalent of Pete Townshend, who, at his best, could record self-produced one-man demos of songs that were nearly the equal of the finished product by The Who, produced by Glyn Johns. Because Morgen spends so much time using Bowie’s voiceovers to trash his ‘80s recordings, there’s no talk about the seminal December 1982 recording sessions for the Let’s Dance album. That’s a huge wasted opportunity, considering the level of the talent playing in Studio A with Bowie at the Power Station in New York, which included Nile Rodgers, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Bernard Edwards, Omar Hakim, and Tony Thompson.

Also, while the footage of Bowie performing a somewhat desultory version of “Heroes” live in London’s Earl’s Court in 1978 is fun, the original studio recording is one of the greatest moments of 1970s pop music recording:

Bowie’s Bookshelf

Another potential theme that Morgen fails to explore is Bowie’s voracious reading habit, as Mark Judge noted in a review titled “Unserious Moonlight”:

Morgen is painting, in broad strokes, the kind of artistic arc that every Western intellectual is said to have followed in the postwar 20th century West. It’s a familiar, if tired, story. The journey began with the Beatniks, then went through the Beatles, got lost somewhere in the 1970s and emerged sober and re-energized after punk. The defiant stance is essential: down with the bourgeois life left behind, forward with dismantling the old ideas about gender, family, home, capitalism and society.

Yet in Bowie’s case, this might be an exaggeration to the point of a lie. Of course Bowie was an avant-garde artist and a brilliant musician. He was the epitome of cool. Yet the singer, painter, and actor also harbored suspicions of revolutionary movements and was deeply influenced by the books he read—books that were often classics of Western literature. An international superstar who lived globally, Bowie was formed by Western culture.

To understand this one can turn to Bowie’s Bookshelf: The Hundred Books that Changed David Bowie’s Life by John O’Connell. Note: these are not Bowie’s favorite books, but the ones that changed his life.

And while this probably isn’t Morgen’s fault, one of the documentary’s many trailers was for the Hindenburg-level gay-themed bomb Bros. But as Gareth Roberts joked in his Spectator World review, Bowie’s “cooption by ‘queer’ is quite ridiculous. He was not a positive role model or celebrating gay liberation in any way — and, let’s face it, he was about as bisexual as Jeremy Clarkson. We can see Harry Styles doing the same pop tease today, only with approximately 99 percent less talent and style.”

Sadly, there are no bonus features on Blu-Ray, despite the miles of footage that Morgen left on the cutting room floor. There’s no director commentary of Morgen explaining and defending his choices, either.

Bowie shared with John Lennon a strange love of ‘70s American talk shows, so as a result, there is a particularly enormous video trove of his interviews, which, coupled with his many filmed live performances, could be assembled into any documentary form a director desires. There is an excellent documentary waiting to be made about the man, but Moonage Daydream isn’t it. Though Bowie diehards will likely love the footage, even if they don’t enjoy every moment of the roller-coaster ride.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member