“Squaring the Circle (The Story of Hipgnosis)” is a 2022 documentary that has recently been released on streaming platforms such as Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video. It was directed by veteran Dutch rock photographer and video director Anton Corbijn, whose work was heavily influenced by Hipgnosis’ house style.

Corbijn’s documentary begins in black and white, with shots of a mysterious middle-aged man with shaved thinning hair and wearing expensive, fashionable black eyeglasses while carrying what looks like a very heavy, very large package on his back stenciled HIPGNOSIS. We hear his footprints as he shuffles past a cemetery and enters a building’s hallway and sits down. After the door closes, Pink Floyd’s elegiac “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” fades in. He then wanders to the end of the hallway where the word HIPGNOSIS has been splashed on the wall, graffiti-style.

The mysterious stranger is introduced as Aubrey “Po” Powell, one half of graphic shop’s founding members. He sits down, and begins to silently, dramatically pull out the items of his makeshift backpack. These are large prints of some of Hipgnosis’ most famous album covers, including Peter Gabriel’s first album, 10cc’s “Deceptive Bends,” Pink Floyd’s “Atom Heart Mother,” ” Wish You Were Here,” and “Dark Side of the Moon.” Using Adobe After Effects, or a similar post-production video compositing software, these prints are shown in glorious full color, even as Powell, who is holding them, remains in stylish black and white. (Everything is in black and white in “Squaring the Circle,” except for the album covers, and scenes of Hipgnosis’ patron bands in concert.)

To understand how significant Hipgnosis’ design work and photography was for rock bands in the 1970s, it’s necessary to go back to the previous two decades. In 1948, the 12-inch long playing record debuted, and by the mid-1950s, jazz artists such as Frank Sinatra and Miles Davis began taking advantage of its extended length to create the first nascent “concept albums.” Prior to the Beatles’ epochal 1967 LP, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band“, album covers were inevitably quite pedestrian, usually with a photo of the performer(s), and in large print, their name, and the album title. But the Beatles’ trendsetting Sgt. Pepper cover, designed by British pop artist Peter Blake, began a nuclear arms race among rock performers to see who could release the most expensive and visually arresting cover.

As a result, for listeners in the 1970s, it became de rigueur to stare at album covers created by Hipgnosis and other graphic designers while playing the LP inside them (and for many listeners, sparking up spliffs of marijuana) and attempt to ascertain the cosmic images and what message the band was trying to send to its fans. In 1982, the compact disc debuted with its 5.59” by 4.92” plastic jewel case, and the small size ensured that the cover artwork became much less significant. Today, album artwork is little more than a thumbnail on a streaming service such as iTunes. But even so, many record labels and artists still agonize over that thumbnail.

“My daughter; she was staying at my house for the weekend,” Noel Gallagher of Oasis tells Corbijn:

“And I said, ‘Oh, sorry I’m late, but I got caught in a meeting in the office about the artwork for my album.’”

“And she said, ‘Artwork? What’s that?!’”

“I told her ‘You know, the artwork. The artwork!’”

“And she said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about!’ Because she’s grown up with the [smart]phone, right?”

“I said, ‘Well, the cover of the record.’ And she was like, ‘The cover? What? What?’”

“And the only way I could explain it to her was to say, ‘You know the tiny little picture on iTunes?’ She said, ‘yeah.’”

“I said, ‘Right. Well, I’ve been in a meeting about that.’”

“She said, ‘They have meetings for that?!’”

“I said, ‘Yes! And it cost a hundred f***ing grand!’”

Before the Big Bang

In the years prior to “Sgt. Pepper,” Powell and Storm Thorgerson were a pair of young artists who were part of the Cambridge “mafia” in the orbit of the band that would become Pink Floyd. In 1968, the two created a design house that they dubbed Hipgnosis, as a shorthand for a pair of hip gnostics creating visually arresting images.

Powell had learned the basics of photography from Thorgerson, and Powell described seeing his first prints develop in the darkroom and getting “goosebumps all over me. I absolutely went ‘Oh my God, this is alchemy,’ and I knew instantly that that’s what I had to do. I would need to be a photographer. I want to be a photographer, and I don’t care what I have to do — this is magic.”

Hipgnosis’ first offices were a converted dance studio at #6 Denmark Street in London, which photographer Jill Furmanovsky describes as “appalling. It was terrible. They didn’t have a toilet, I think they just had a sink. You’d think, ‘How did such polished work come out of such a dump?’” Aubrey Powell says that the former dance studio had a very expensive grand piano that was left in it, which he was able to sell, and which paid for the firm’s first cameras, lighting equipment, and darkroom. “It was a gift from God, and the biggest mistake we made was that we still used a bath, a proper bath, to wash the prints in. And of course, that was a disaster, because not long after we’d been there, the prints clogged up the bath; it overflowed over a long weekend, and flooded the antique Greek bookshop underneath us, causing tens of thousands of pounds worth of damage. Luckily, we were insured!”

Hipgnosis started slow, primarily doing early artwork for Pink Floyd, but by 1973, they became the album cover specialists for British superstar and wannabe star prog rockers. That year, they created the artwork for three massive hit albums, Led Zeppelin’s “Houses of the Holy,” Paul McCartney’s “Band on the Run,” and the mac daddy of them all, Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon,” which spent a staggering continuous 981 weeks on the Billboard charts and sold a total of 25 million copies — and counting.

Who created the word “Hipgnosis?” Powell says that it was Syd Barrett, who wrote it with a ballpoint pen on the door of the flat they were sharing. Others interviewed for “Squaring the Circle” say it was Cambridge-based photographer Dave Henderson, or poet and friend Adrian Haggard.

Powell and Thorgerson formed a remarkably symbiotic team. Powell was largely the in-house photographer, and Thorgerson the prickly conceptual artiste, with an ego and temper to match. When Paul McCartney was wrapping up the recording sessions of his 1975 album “Venus and Mars,” he flew Powell and Thorgerson out to L.A. to explain he want to have yellow and red billiard balls representing the two planets. Powell says, “I have to say, when you get a call from a Beatle, it was a bit like getting a call from God.” In contrast, according to Powell, Thorgerson responded:

“I’m not interested in this, Paul. I’m not interested in your idea. So, I’m going to leave L.A., and Po can do it.” There was a slight stunned silence and then Paul said, “Okay, man, that’s fine! You go home; Po can deal with it. He’s the photographer, anyway, right?”

When we got back to the hotel, I said to Storm, “Was that really the right approach we should have?” And Storm said, “If I can’t do Hipgnosis ideas, I don’t want to do it.”

This is followed by numerous former Hipgnosis employees explaining how difficult, rude, and cantankerous Thorgerson could be to work with — and as can be witnessed above, even with superstar clients. As Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason tells Corbijn, “Storm Thorgerson was a man who would not take ‘yes’ for an answer.”

Perfecting the Inherently Imperfectible

“Hipgnosis,” is a portmanteau of the words “Hip” and “Gnostic,” the latter of which, Jonah Goldberg, then with National Review Online, defined in 2002 thusly:

Gnostics were pre-Christian, early Christian, and various Jewish sects who believed that if you stood on one foot while saying the alphabet backwards, or some other silliness, you could release your soul from material constraints while you were still alive…Gnosticism took many forms, in many places, over many distinct periods (sort of like bell-bottom pants). The central thing to keep in mind is that Gnostics believed that personal enlightenment — or revelation to a specific truth or viewpoint — liberated you from the need to find salvation in the afterlife or through any conventional, institutional means. Instead of going to salvation, they brought salvation to them…It’s not surprising, then, that the Catholic Church was constantly putting out Gnostic fires through most of its history.

Because the Gnostics believed they — and they alone — had figured out God’s plan in the here and now, they tended to be very, very smug and more than a little annoying (except when they were on the rack, which tended to make them a lot less smirky). It also inclined Gnostics to argue that heaven could be established here on earth, that through material or political means they could perfect the inherently imperfectible.

Certainly, feeling smug and (at least paying lip service to) creating heaven here on earth were very much the goals of almost every rock band from the mid-‘60s until the mid-‘70s, and not without its share of casualties along the way.

The Return of the Prodigal Syd

Pink Floyd’s follow-up album to “Dark Side of the Moon” was 1975’s “Wish You Were Here,” inspired by Floyd founding member Syd Barrett becoming one of rock’s most prominent LSD casualties. Because of their deep connection with the members of the Floyd, Thorgerson and Powell witnessed Barrett’s rapid decline up close and personal. Powell recounts the legendary story of a fat, bald and dissipated Barrett stumble into his former band’s recording sessions for “Wish You Were Here,” Waters’ encomium to Barrett. As Powell tells Corbijn:

I was in Hipgnosis’ studio one afternoon, and there was a knock at the door…and there stood this dumpy, fat man with a shaved head, which had obviously been shaved by himself, because it was all kind of raggedy…[after ascertaining it was Syd Barrett], I said ‘what can I do for you? Come in! Come in!’

He said, “Are the band here?” I said, “No, no, they’re not. Do you want to come in and have a cup of tea?” He said, “No, no,” and disappeared down the stairs. And of course, then he showed up at Abbey Road Studios, and nobody recognized who he was.

Roger Waters: “Dave [Gilmour] looked at me and grinned and said, ‘You haven’t got it yet, have you?’ And in that moment, I went, ‘F**ck me — it’s Syd!’ That fat, bald bloke with a brown paper bag. And of course, it was.”

While Barrett was of the earliest and most visible examples of the dangers of excess drug use, he was far from the only rock star damaged by an excess of drugs and/or booze. By 1977, Jimmy Page was so drugged out he was playing in a remarkably sloppy fashion during numerous concerts throughout Led Zep’s tour of the US, and Roger Waters was so angry at the rowdiness of Pink Floyd’s newfound stadium audiences that he ended the last show of the tour in Montreal that year spitting on a particularly unruly fan in the front row.

By this time, the Summer of Love could just barely be seen in the rearview mirror as it retreated further and further away far into the distance.

Not coincidentally, the flailing nature of the dinosaur rockers ensured that the revolution of nihilistic punk rockers and back-to-basics new wavers and pub rock bands would arrive to fill the void.

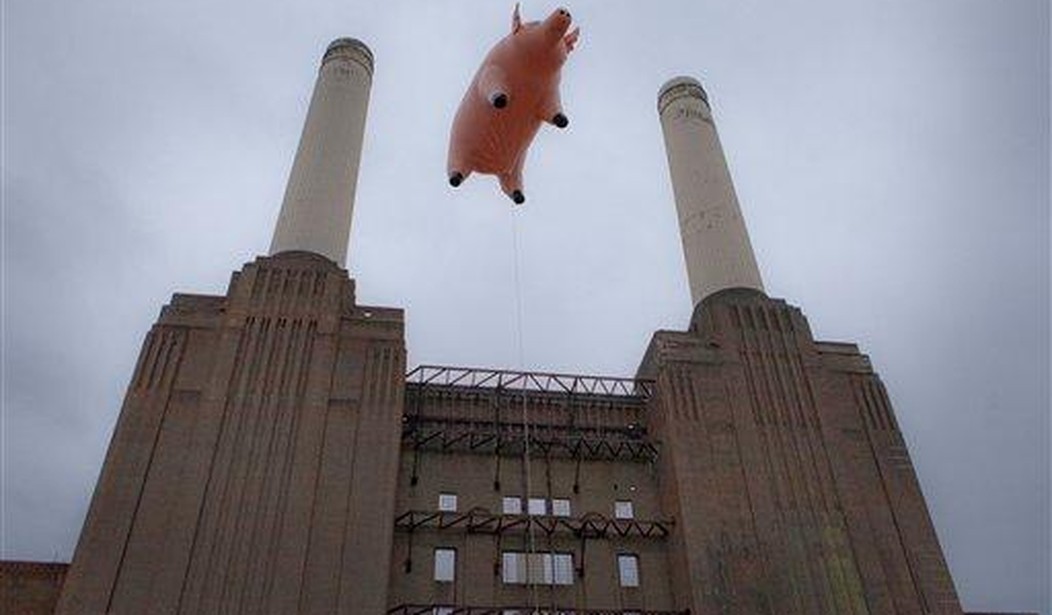

1977 was also the year that Waters conceived of the Floyd’s now legendary cover for their album Animals, featuring a giant inflatable pig flying over London’s Battersea Power Station. While the Hipgnosis team was responsible for the execution of Waters’ brainstorm, unfortunately, Thorgerson began to take credit for creating the concept himself, resulting in a long falling out between himself and Waters, two of the rock world’s largest and most volatile egos.

Keeping the Zeppelin Aloft

After designing the cover for Led Zeppelin’s 1973 album “Houses of the Holy,” the ambition of Hipgnosis’ last covers for the group helped to mask the band’s slow decline, thanks to the aforementioned drug-fueled dissipation of guitarist and band leader Jimmy Page and drummer John Bonham.

Taking a cue from the Monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” Powell designed the cover for Led Zeppelin’s 1976 album “Presence” to feature numerous shots of teachers, doctors, and the stereotypical nuclear family posed around a small black “obelisk.” The goal was to symbolize how ubiquitous Led Zeppelin’s music had become, while also implying the mysteries and mysticism that the band maintained. This was originally a straight narrow black block on a base; it was Jimmy Page who suggested giving the shape its now iconic twist in the middle. Page tells Corbijn, “Well, it was right; it was the right decision — crikey, it got emulated on a [skyscraper] in Dubai!”

For “In Through the Out Door,” Zeppelin’s last album as a group before Bonham’s death in 1980, Hipgnosis spent a fair amount of the band’s promotional budget recreating on a London soundstage a near-exact replica of the Old Absinthe House, a funky New Orleans bar. Sitting at the bar is a male model in a white suit and fedora who strongly resembles Page, burning the “Dear John” letter he had just received from his girlfriend. “It was probably the most expensive album cover we had ever done, because it was so complex,” Page tells Corbijn.

Taking a cue from Welles’ Citizen Kane and Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Hipgnosis photographed the scene from the perspective of the various actors in the room, portraying such archetypes as the bartender, the prostitute standing by a jukebox, the piano player, and the waiter, resulting in six album covers.

The customer had no way of knowing which cover he was buying, thanks to a grousing comment by Zep manager Peter Grant. Frustrated by the expensive photoshoot required to produce Hipgnosis’ elaborate concept, Powell says that Grant told him, “‘We could put the album in a brown paper bag, and it would f**king sell.’ I said, ‘Peter, what a great idea.’ Atlantic didn’t want the aggravation, but Peter said, ‘We’re f**king doin’ it.’”

As a result, the six scenes depicted on the cover were hidden inside brown paper bags labeled “LED ZEPPELIN, IN THROUGH THE OUT DOOR” in a tiny stamp in the upper left-hand corner of the bag. Grant was of course absolutely right, as the first new studio album by Led Zep in three years went on to sell six million copies in the US, reactivating sales of much of Zep’s back catalog as well. As Mitchell Fox of Swan Song Records noted in 2012, In Through the Out Door “went on to debut at No. 1, with eight other catalogue albums entering the Top 100. That meant that Zeppelin owned 10 percent of the chart.”

Looking back at In Through the Out Door in the hindsight of over 40 years, Page admits on camera that “The [bar] set was better than the album!” And while In Through the Out Door was one of my favorite Zeppelin albums, plenty of critics and fans would agree with Page’s assessment.

Coda

The early 1980s, with its emphasis on post-punk “new wave” rock groups, and the arrival of MTV created a very challenging environment for Hipgnosis. Progressive rock groups and expensive album cover shoots were largely relegated to the sidelines. Storm Thorgerson decided he’d rather be rock video director instead, but within two years, Hipgnosis was deeply in debt, and was forced to disband. For 12 years, Storm and Po didn’t speak to each other, much to the latter’s on-camera shame in Squaring the Circle.

Storm and Po continued to create album covers though, particularly for their early patrons, Pink Floyd. Thorgerson took a simple line from a song by David Gilmour for 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason, the first album of the Floyd sans Roger Waters and created a typically mind-blowing Hipgnosis-style shoot, as Mark Blake wrote in his 2007 band history, Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd:

The last piece of the puzzle would be artist Storm Thorgerson, whose last proper Pink Floyd commission (excluding [the 1981 greatest hits collection] A Collection of Great Dance Songs) had been 1975’s Wish You Were Here. ‘I was brought back to help give Momentary Lapse … a Floyd look and a Floyd feeling,’ said Thorgerson. Inspired by a lyric from the new album’s ‘Yet Another Movie’ (‘a vision of an empty bed’), Thorgerson suggested staging a scene of 700 empty beds arranged on a beach. ‘David said, ‘Sure, just do it,’’ recalls Thorgerson. They transported the props to their chosen location, Saunton Sands in North Devon, and laid out the beds one by one. Then rain stopped play. The photograph was finally taken a fortnight later. It was a suitably grand and expensive concept for what would be a grand and expensive album and tour.

Thorgerson died in 2013. However, his former business partner is still very much creating new artwork, and video as well. For the Floyd’s 2019 super-deluxe retrospective of the post-Waters era, The Later Years 1987-2019, Aubrey Powell created the box set’s cover art, and completely re-edited the footage that was originally earmarked for the 1989 in-concert video, The Delicate Sound of Thunder, once looking rather murky and slowly paced, now looking stunning in 4K high-definition video.

For fans of 1970s prog rock, Squaring the Circle will be a nostalgia-fueled look back at a particular era in the recording industry, when ambitions were high, and marketing budgets even higher. For those looking for inspiration for their own graphic designs and photographic compositions, there is much to learn here. For those who want to look back in astonishment at arguably rock’s most debauched era, there is excess to burn on display here. In any case, a highly recommended documentary.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member