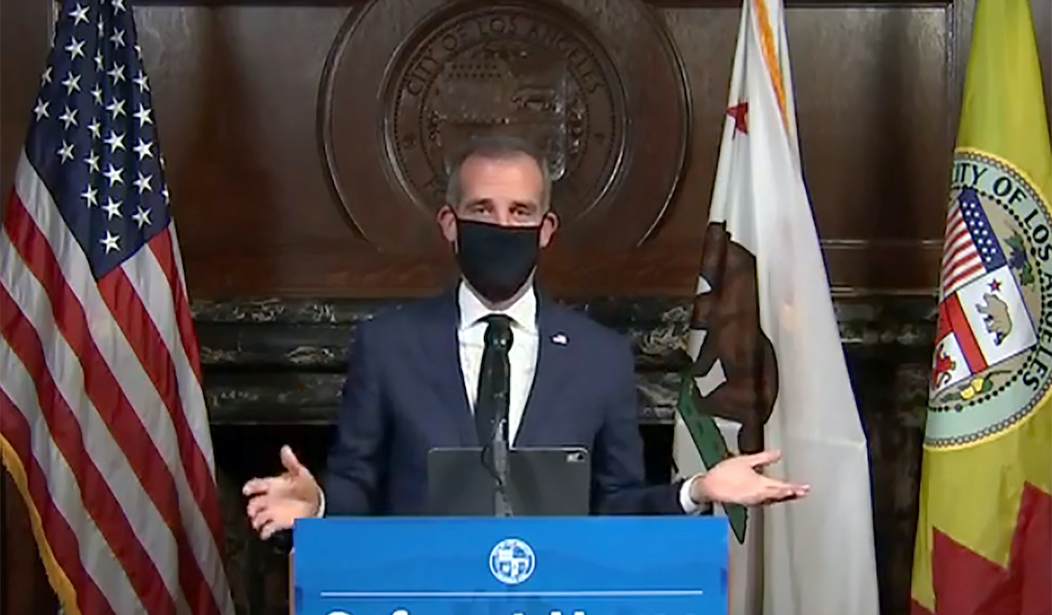

As Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti prepares to depart for India, where he will take up his duties as our new ambassador, he offers a parting shot that will further degrade the city that has already suffered so under his tenure. Recall that when Garcetti first ran for mayor in 2013, he vowed to end homelessness in Los Angeles within ten years. No one living or working in L.A. needs to be told how miserably short of this goal he came, but for those outside Southern California, NPR reported in 2020 that there were 41,290 homeless people in the city of Los Angeles and 66,433 in L.A. County, increases of 14.2% and 12.7%, respectively, from the previous year.

Not unrelated is the issue of crime in L.A., which has increased in recent years after a long period of decline. There were 397 homicides in the city last year, a 50% increase from two years ago and a 15-year high. And yet, as Garcetti leaves the city, he gives the back of his hand to the already demoralized Los Angeles Police Department.

The headline on a Thursday Los Angeles Times story reads, “Garcetti questions LAPD discipline for out-of-policy police shootings, orders review.” In the article, Garcetti laments that some LAPD officers are not punished as severely as “elected officials and police leaders” would wish after violating department use-of-force policies. This occurs, says Times writer Kevin Rector, “because discipline panels hand down lesser penalties — sometimes leaving officers who officials want to fire on the force.”

All LAPD use-of-force incidents are investigated by the department, with the intensity of the investigation varying with the seriousness of the incident. A minor altercation resulting in little or no injury to the officer or suspect is investigated by the officer’s immediate supervisor and reviewed within his chain of command. When an officer shoots someone, it is investigated by specialized detectives responsible for only such cases, who produce a report to be reviewed at several levels within the department, including the chief, the civilian police commission, and the independent inspector general.

When an officer is found to have violated policy, a personnel complaint is generated and, if the violation is deemed serious enough, the officer is sent to what is known as a board of rights, a quasi-judicial hearing at which three people hear the evidence. If the charge against the officer is sustained, the board hands down a punishment ranging from a reprimand to termination. Years ago, all three members of these boards were senior LAPD officers at the rank of captain or above. In 1992, civilian members replaced one of the three officers, and in 2019, accused officers were given the option of having an all-civilian board hear their cases.

Garcetti finds it objectionable that all-civilian panels have often been lenient with accused officers, refusing to terminate them as those “elected officials and police leaders” would have preferred. Rector makes brief reference to internal LAPD dynamics in addressing this issue. He writes: “[O]fficer-led panels—composed of top cops seeking to climb the ranks—are less likely to buck a chief’s recommendation of severe punishment.”

Related: Los Angeles Rocked By Recent Railway Robberies

This deserves more discussion than Rector gives it. As I’ve written before, there are three basic types of police officers. The first and most important are those most dedicated to the job and most proficient at it. These officers rarely advance beyond the rank of lieutenant. The second group is made up of the “climbers,” i.e., those who may or may not be proficient at actual police work, but who plan their careers with an eye toward advancement up the ranks, preferring administrative duties to any that may require them to get their uniforms dirty. The third group is made up of the slugs, those who show up and do their time, collecting their biweekly paycheck with a minimum of intellectual or physical exertion. In too many cases, being a member of this group is not a bar to promotion.

No one in the LAPD advances to the next rank without at least a tacit blessing from the chief of police, and at the higher ranks, an overt endorsement is required. Chief Michel Moore, like his counterparts in any major city you can name, keeps his moistened finger in the air, keenly sensing any shifts in the political winds. When politics demands an officer’s head on a spike, Moore believes it his duty to deliver. Thus, any captain or other senior officer commits career suicide if he fails to recommend termination for an officer Moore has found politically expendable.

This presents a dilemma for cops on the street, who know that a certain aggressiveness is required if rising crime is to be stemmed but also that violent crime in Los Angeles, as in every other major city in America, is committed largely by so-called “people of color,” on whom has been conferred in the current culture something approaching an outright license to resist arrest. Yes, cops are told, please go out and arrest lawbreakers, but do it without hurting any of them. These goals are mutually exclusive, and the current rise in crime reveals it is the latter being advanced at the expense of the former.

So, as Eric Garcetti jets off to India, he can do so while enjoying the fantasy that the quality of life in Los Angeles has improved during his tenure as mayor. Those he leaves behind, meanwhile, remain stuck in the grim reality he helped bring about, one that will be made even worse by his latest insult to the men and women of the LAPD.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member