To the debatable extent President Biden was sincere in his remarks about policing during his State of the Union speech Tuesday evening, and for that matter, to the even more debatable extent he was able to comprehend what he was reading from the teleprompter, we can be grateful the speech signaled an end to the defund-the-police madness to which so many have succumbed in recent years. But even if every police department in America were funded to their pre-George Floyd-hysteria levels and beyond, the crime increases seen in many cities will likely continue.

For Our VIPs: Biden Wants Us to Forget He Embraced Defunding the Police

Why? Because funding is but one factor contributing to a police department’s effectiveness. An underfunded department will be hamstrung in certain respects, of course, but even the most lavishly budgeted department will fail to lower crime if it operates in a political environment hostile to that goal. Sadly, the cops in many American cities find themselves working in just such an environment.

Los Angeles is one of those cities. On Tuesday, the Los Angeles police commission, the civilian body that oversees the LAPD, approved restrictions on “pretext stops,” in which minor violations are used to look for evidence of more serious crimes. In enacting the new policy, the commission places burdens on LAPD officers not required by statute or case law. Indeed, the policy ignores the clear language of the U.S. Supreme Court case of Whren v. United States, which held that “[t]he temporary detention of a motorist upon probable cause to believe that he has violated the traffic laws does not violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable seizures, even if a reasonable officer would not have stopped the motorist absent some additional law enforcement objective.”

The new policy does not, in the strictest sense, establish a prohibition on making pretext stops. Instead it imposes the requirement that officers articulate their suspicions for such stops on their body cameras. But unlike the concept of “reasonable suspicion” for a detention, which was first advanced in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Terry v. Ohio, there is no established standard for evaluating any individual officer’s suspicions as they relate to pretext stops, so enforcement of the policy will be subjective. And given that no one on the police commission, and few in the LAPD above the rank of sergeant, have even the first clue about how police work is conducted in the field, I anticipate this policy to be used as a weapon against officers who find themselves in disfavor with their superiors.

Revealing a dismaying level of ignorance on the matter was William Briggs, president of the police commission, who told the Los Angeles Times that there “is no data that anyone can point to that establishes pretextual stops curtail violent crime in our city.” Briggs, an entertainment lawyer with no criminal law experience, further betrayed his lack of understanding by citing a review by the LAPD’s inspector general that comported with an L.A. Times investigation on stops made by officers from the Metropolitan Division. That investigation, says the L.A Times, showed that officers stopped black drivers “at a rate more than five times their share of the city’s population.”

With this, the L.A. Times persists in advancing the fiction that crime and police-stop statistics should reflect the city’s overall population. They might in the future consult their own Homicide Report database, which reveals that of the 728 people killed in Los Angeles County in the last twelve months, 257, or 35%, have been black. Given that nearly all murders are intra-racial, and given that the population of Los Angeles County is 9% black, it is plain enough that blacks are responsible for more than their share of L.A.’s violence. Thus, any law enforcement efforts to address that violence will have a similarly disproportionate effect on them.

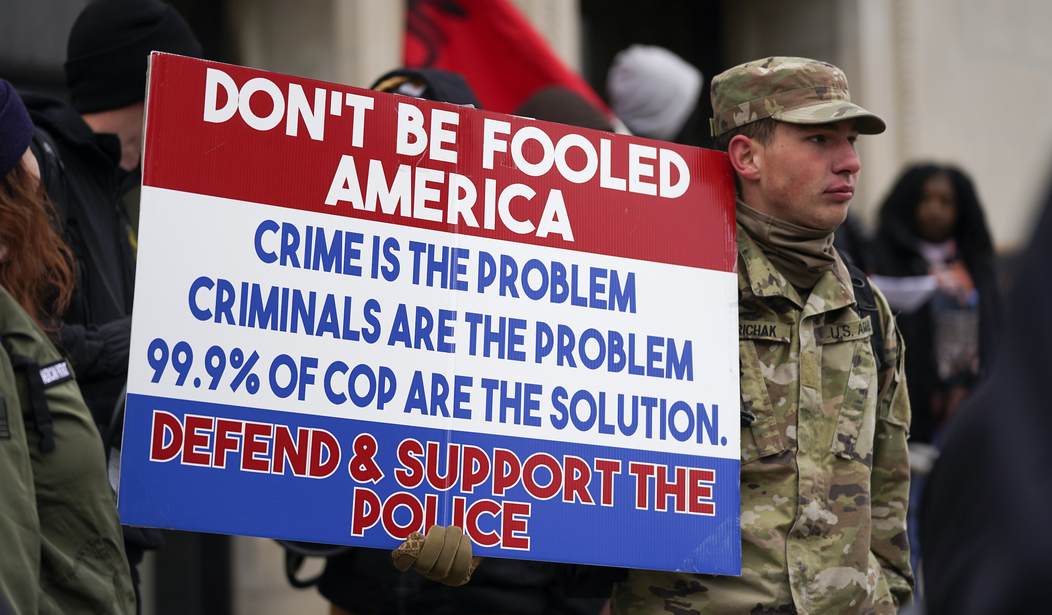

Homicides in Los Angeles are down 15% so far this year (though still up 20% from two years ago), but the more violent months of summer lie ahead. LAPD cops already work under the burden of knowing George Gascón, their “progressive” district attorney, is eager to prosecute them for any perceived transgression. With this new policy, they have been sent another in a long series of messages that their overseers think it is they, not the criminals, who are the problem.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member