A panel at the United Nations on Wednesday unveiled the horrible science and terrifying results of U.N. population policy. While well-intentioned, the UN’s efforts to bring the Third World out of poverty are based on some very faulty assumptions, and they end up producing disastrous consequences for women abroad, particularly in Africa.

The type of contraceptive which the UN suggests for African women is very controversial. There is evidence that it increases their chances of contracting AIDS by 40 percent, doubles the likelihood they contract breast cancer, and likely causes significant bone deterioration.

The UN does some very funny things when interpreting data from foreign countries. It considers “deaths averted” nearly the same thing as “lives saved,” claiming that if many babies are never born, then their lives are effectively saved. The global organization also monkeys with surveys of African women, taking the soft statement that they don’t want to be pregnant right now as evidence that they have a demand for contraceptives.

The UN is “putting words in women’s mouths,” explained Rebecca Oas, associate director of research for the Center for Family and Human Rights (C-FAM). She referenced the widely quoted statistic that “over 200 million women want access to contraception but are unable to get it,” arguing that this statement twists the truth by defining terms badly.

Oas, who holds a doctorate in genetics and molecular biology from Emory University, applied her expertise in analyzing hard scientific data to explain why the UN’s approach to social science is so wrong.

“A lot of advocacy relies on adequate data,” she said. “One of my concerns is that, as much as we want this agenda to be inspirational and aspirational, the indicators have to not be aspirational.” The numbers explaining the situation in the world have to accurately represent the good and the bad, in order for advocacy to do its work. “Advocacy cannot be integrated in the indicators,” Oas explained. “We have to measure what actually is.”

Bad Data on Contraception

When it comes to the actual facts, there aren’t 200 million women who want contraception but do not have access to it. That number was based on household-level surveys of married women of reproductive age, who were asked one question: would they prefer to become pregnant in the next two years. “The researchers did not ask if she wants family planning,” Oas pointed out.

Next Page: Why this difference is so important, and how the UN is biased in favor of birth control.

AEI’s Alex Coblin and C-Fam’s Rebecca Oas and Stefano Gennarini at the United Nations. Photo Credit: Tyler O’Neil, PJ Media

When a woman says she would prefer not to become pregnant in the next two years, she is not saying very much. A study between 1998 and 2003 revealed that many of the women expressing a wish not to become pregnant also added that it would be “no problem” or a “small problem” if they became pregnant. However, the question is a simple yes or no. When the woman says no, it is assumed she wants birth control, even though many women have various objections to it.

“A woman’s stated desire to avoid pregnancy is taken as a mandate, but a woman’s decision to not use contraception is regarded as a ‘barrier,'” Oas explained. In other words, there is a latent bias in the way the UN asks these questions and interprets the answers. Researchers take a simple preference and transform it into a “demand” for birth control.

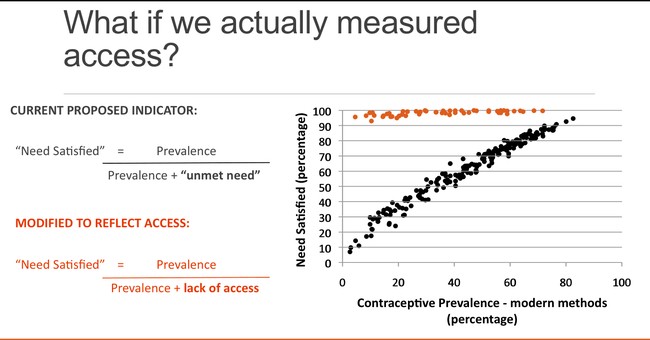

Furthermore, the UN defines “unmet need” with a convoluted mathematical formula which hides the fact that contraceptives are widely available for women across the world. Oas presented a graph with the UN’s data showing the percentage of “need satisfied,” along with her own calculation on basic access to birth control, illustrating the absurdity of claiming that birth control is difficult to come by.

Because people think that there is a huge unmet need for birth control, due to this bad data, they invest billions of dollars into contraceptives, while taking money away from maternal and child health services.

“Deaths Averted”

Another convoluted use of data involves the argument that increasing contraceptive use will “save lives.” Oas quoted a joint statement made in March 2015 by philanthropist Melinda Gates and Graca Machel, widow of the late South African President Nelson Mandela. “In fact, if the world extended contraceptive use to only a quarter of the women with an unmet need, it could save the lives of 25,000 women and 250,000 newborns each year,” the women wrote.

Wait — how does contraceptive use save the lives of newborns? Oh yeah, it prevents them from being born. That’s right, the UN considers it a “life saved” when a baby is not conceived, so long as infant morality in the region is high.

There are many problems with this approach, foremost the assumption that women will use the contraceptives, and that current rates of maternal and infant morality will remain constant.

Oas argued that this creates a perverse incentive. “The more risky it is to have a death from a birth, the more you can claim to have saved lives” by preventing those births in the first place. The researcher responded, “I say we should make childbirth safer, not more rare.”

“Make birth safer for both mother and child — I would urge caution when measuring hypothetical effects like ‘deaths averted,'” Oas declared.

Next Page: The kind of contraception matters — how the UN is pushing dangerous birth control on African women.

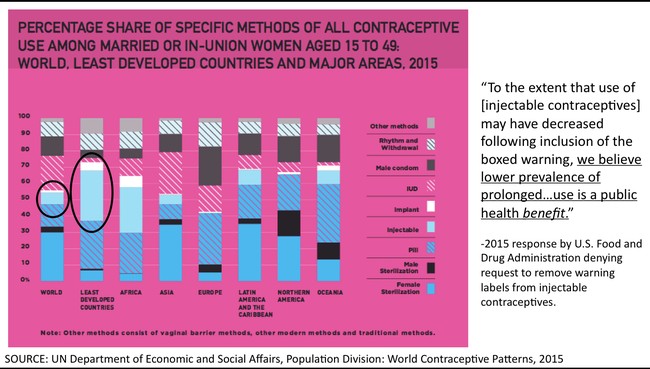

Furthermore, Oas explained that the UN pushes injectable contraceptives in African countries, a form of birth control that is barely used at all in other parts of the world. African women’s “concerns about health risks are treated as ‘myths’ and ‘misinformation,'” Oas noted, but in places where these contraceptives are prevalent, “their fears are likely to be based on actual experience of their neighbors.”

Because the UN does not take these concerns seriously, Oas alleged, the researchers make “no effort to evaluate the truth of these claims,” many of which “had a real basis in medial evidence.”

Injectable contraceptives have been associated with increased cancer risk, increased risk of HIV transmission, and a decrease in bone density. “Some of the types of family planning which have the greatest health risks are heavily promoted in developing countries,” Oas explained, noting that the United States Food and Drug Administration said that reducing the use of injectable contraceptives would be considered “a public health benefit.”

Why is the UN So Obsessed with Birth Control?

The UN focuses on birth control due to many wrong-headed factors. In addition to the clumsy concept of “unmet need” for contraception and the idea of counting “deaths averted” as lives saved, the global body connects the notion of a “demographic dividend” with falling fertility rates. Alex Coblin, senior research associate at the American Enterprise Institute, explained why the UN thinks this way and why it is overly simplistic.

The idea goes like this: As countries become more developed in science and technology, they find cures for various causes of death. This allows more children to survive infancy and more adults to live longer in old age, resulting in a population boom that ends up causing big economic growth. At the same time, women start to have fewer children which means that over the long run, fewer people (women in particular) are focused on childcare and are freed up to enter the workforce.

The population spikes, and then it falls. The UN’s theory is that providing contraception not only averts the likely deaths of mothers and (now non-existent) babies, but also helps this transition and leads to economic growth.

Next Page: Why this view is so wrong, and the greatest threat to global economic growth in the coming decades.

Coblin explained that this idea is too simplistic, however. The huge spike in economic growth has more to do with the benefits of science and technology for people of working age, and less to do with decreasing fertility rates.

“The population boom is not due to people mating like bunnies, but people not dropping like flies,” Coblin insisted. The problem in undeveloped countries is not women who give birth too frequently, but that there isn’t enough investment in “human capital,” the things that make workers more effective.

“The demographic dividend is not just due to the drop in the birth rate, but also to many issues, such as education and health,” the scholar insisted. He suggested a model which analyzes four factors: life expectancy, average years of schooling, how much of the population lives in big cities, and economic freedom. In his analysis, 80 percent of economic growth differences are captured by those four factors, which have nothing directly to do with fertility rates.

Coblin also emphasized the importance of sub-Saharan Africa as the region from which most of the world’s future workforce will come. Between 2010 and 2035, the region is projected to have a 2.92 percent annual growth rate among people ages 15 to 64, considered the working-age population. For comparison, he noted the growth rate of East Asian countries during their economic boom, a mere 2.4 percent annually.

A 2013 IMF report estimated that in 2035, the number of people reaching working-age in sub-Saharan Africa will exceed that of the rest of the world combined.

Nevertheless, the entire world is starting to face demographic decline, as more and more developed countries fall below replacement level. Rather than pushing birth control, the UN should start to consider how we should address the issues of an aging population.

Both Oas and Coblin insisted that this is the real issue of our time, and that the United Nations’ focus on pushing contraception for women in Africa is not only dangerous to those women, it risks hiding the largest struggle developed nations face going forward.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member