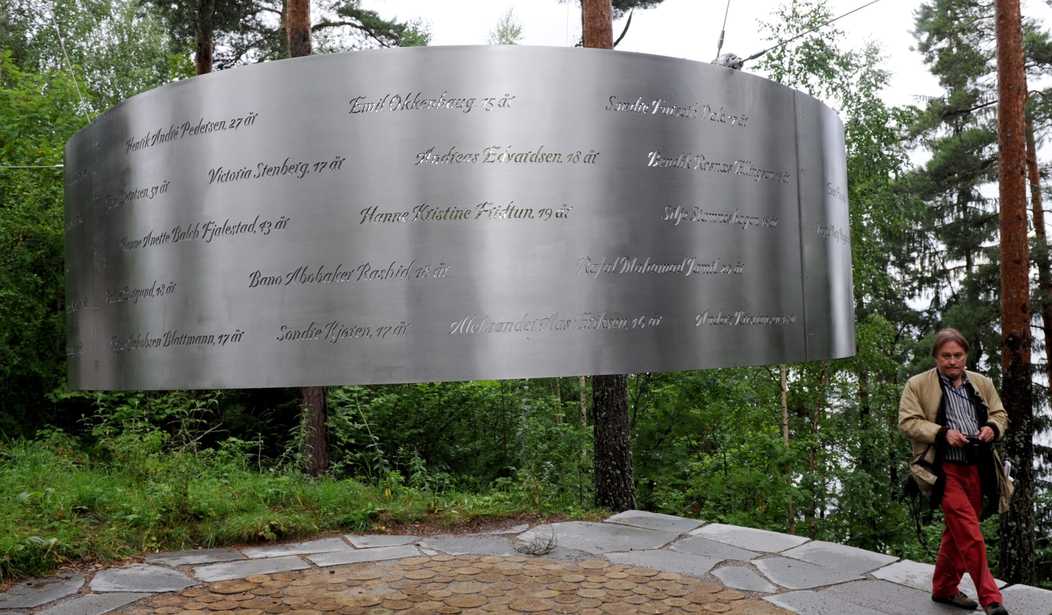

Just out on Netflix, Paul Greengrass’s new film, 22 July, takes its title from the date in 2011 on which a lone maniac named Anders Behring Breivik murdered seventy-seven people in Norway. But only the first third or so of the movie covers the actual events of that date – the massive explosion Breivik set off in a parked panel truck outside the major government building in Oslo, killing eight, and the shootings he then carried out at the ruling Labor Party’s annual summer youth camp on the nearby island of Utøya, which took sixty-nine lives. The second third of the movie depicts the aftermath of the atrocities and the preparations for Breivik’s trial, and the third focuses on the trial itself.

If the film divides into three distinct acts, it also has three distinct plot lines. One of them focuses on Viljar (Jonas Strand Gravli), a teenage boy from the Arctic island of Svalbard, where his mother is the Labor Party’s candidate for mayor. We first glimpse him in a political seminar at Utøya, where he stands up in front of his fellow campers and talks about how multi-ethnic Svalbard is and how well everyone there gets along and works together. A few minutes later he, his brother, and some of their friends are running through the woods being shot at by Breivik (Anders Danielsen Lie). Viljar sustains several wounds and, after Breivik’s capture, survives extensive surgery only to confront, in the succeeding months, a bad case of PTSD.

Another narrative focuses on Jens Stoltenberg (Ola G. Furuseth), the then prime minister of Norway, who after July 22 sets up a commission to investigate what had gone wrong. Why, he wants to know, hadn’t Norwegian intelligence known about Breivik, who had been accumulating bomb ingredients for a long time without detection? Also, how had he managed to kill so many people before being stopped?

A third plot line concerns Geir Lippestad (Jon Øigarden), the Oslo lawyer and Labor Party member whom Breivik selects as his defense attorney. Examined by a team of psychiatrists, Breivik is judged to be insane, and at first agrees to plead accordingly. But he then decides to challenge that diagnosis and to take full responsibility – or, in his eyes, credit – for his actions. He doesn’t want to be seen as a maniac, he informs Lippestad, but instead wants to be recognized as a thoroughly sane person who committed a thoroughly sane, indeed courageous, act.

Breivik’s explanation for his bloodbath is this: the Norwegian government, with the Labor Party at its helm, has flooded Norway with unassimilable Muslim immigrants whose alien values and culture makes them an existential danger to the nation. The leaders of the Labor Party, he charges, are traitors to their country; if he set out to slaughter their children at Utøya it’s because, he says, he wanted to hit these traitors where it would hurt them the most.

At first Lippestad argues with Breivik: doesn’t he realize that pleading guilty will land him in jail for life? Breivik doesn’t care. He wants his day in court. That settles it: Lippestad has no alternative other than to figure out how to get around the insanity diagnosis and present Breivik as sane. Conferring with his defense team, Lippestad comes up with a new approach: he’ll argue in court “that only someone rational could have planned and executed something this complex.” Moreover, he’ll “look into the far right and find witnesses who share his beliefs, so we can show that he’s not alone in his views.”

To this end, Lippestad pays a visit on a fellow who goes unnamed in the film but who is represented as a full-fledged neo-Nazi type with links to extremist organizations around the world. Lippestad politely asks him to testify in Breivik’s defense. He agrees. In court, the neo-Nazi says that he supports violent revolution, but rejects Breivik’s pointless one-man mayhem. Who is this supposed to be? In point of fact, a couple of neo-Nazi types testified at Breivik’s trial, along more or less the same lines as the guy in the movie. In the film, in any event, Breivik is wildly dissatisfied with this one fellow’s testimony: in a tête-à-tête with Lippestad, the murderer demands to know why aren’t there more people testifying on his behalf. Surely millions of Europeans support his actions! Lippestad replies that he could only wangle this one witness.

Greengrass, the British director of United 93, Captain Phillips, and several Jason Bourne pictures, has said that he was determined to make 22 July as fact-based as possible. But this part of the film severely distorts the truth. In reality, Lippestad called a number of critics of multiculturalism – not just far-right nuts marinated in racial hatred, but serious mainstream writers and commentators – as “expert witnesses.” I was one of them, and at the time I was in regular contact with several of the others. Pace the film, Lippestad didn’t ask any of us, politely or otherwise, whether we’d be willing to testify. Instead we were sent summonses in the mail, ordering us to testify or risk imprisonment. The purpose of all this was instantly clear to me: some people in Norway’s corridors of power didn’t just want to put Breivik on trial. They wanted to adjudicate the very act of criticizing Islam and mass immigration.

One of us, Hanne Nabintu Herland, a respected historian of religion, refused to obey the summons and wrote an op-ed explaining why: ever since July 23, she declared, the Labor Party had been playing a “cynical political game,” seeking to crush its own critics by equating them with Breivik himself, and that this “political witch hunt” had reached “totalitarian” levels. Yep. That’s precisely what happened – no exaggeration. For a while there, it got pretty ugly. I wrote a whole book about it. And Greengrass’s film doesn’t so much as hint at any of it. I was preparing to follow Herland’s example and write my own op-ed announcing my refusal to testify when I was advised by an attorney that, under Norwegian law, no one could be compelled against his will to serve as an expert witness. In other words, the summons sent to me, and those sent to others, had been entirely illegitimate. Plainly, someone was trying to pull a fast one.

None of this makes it into Greengrass’s film. Throughout, he portrays Lippestad as a supremely decent, even heroic guy – a lawyer who despises everything his client stands for, but who believes in even a mass murderer’s right to a proper defense. We’re encouraged repeatedly to feel for the poor, put-upon defense lawyer – who, because he’s accepted the job of defending Breivik, gets called a Nazi by strangers and is asked to remove his child from a day-care center.

As for Stoltenberg, although his government is ultimately savaged in the commission report about the Breivik murders – which concludes that the whole nightmare might have been averted but for major failures of leadership, communication, and resources, not to mention unforgivably slow police response and a total unavailability of helicopters in the nation’s capital – Greengrass goes ridiculously easy on him too. Painting him from start to finish as a noble, high-minded sort, the director actually proffers a late third-act scene in which a cabinet official comforts the brooding PM, gently assuring him that the deaths on July 22 weren’t his fault but Breivik’s, and that Norway needs his leadership now more than ever. Give me a break.

In the end, then, 22 July sends a nice, tidy message. On one side, all the Labor Party folks – the champions of multicultural values – are good guys, the salt of the earth, the heart and soul and conscience of Norway. And on the other side, of course, there’s Breivik, whom Greengrass comes uneasily close, when all is said and done, to depicting as a sympathetic misfit, a hapless victim of a malicious international movement, a sad sack whose patently mad butchery of scores of children we’re invited to see as well-nigh inextricable from sane, reasonable, fact-based views of the Religion of Peace.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member