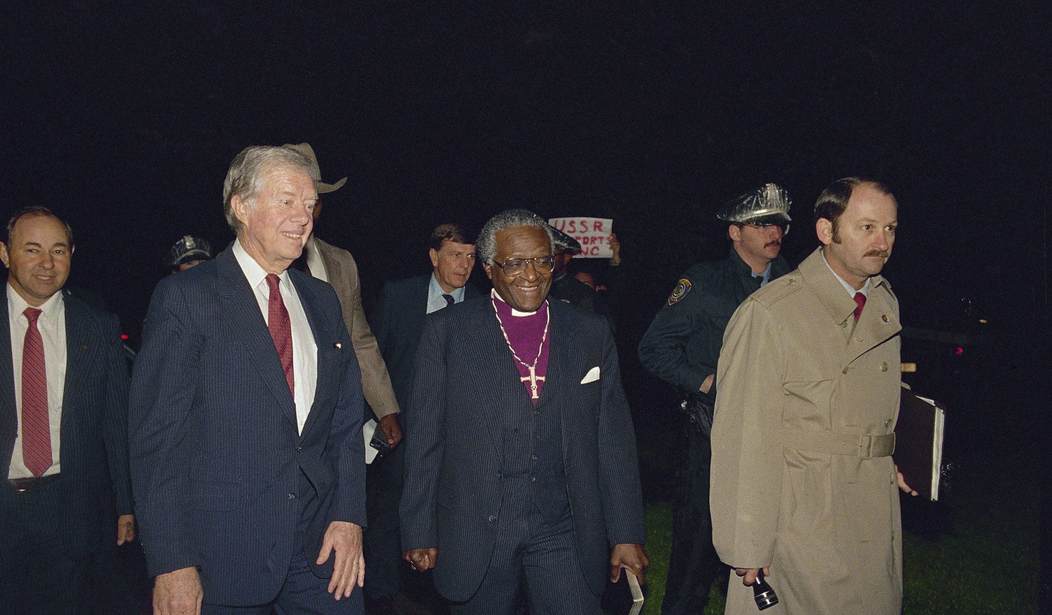

Once upon a time, a large framed photograph of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu hung on the wall of my living room in Manhattan. I wasn’t the one who put it there, but I never felt a moment’s inclination to take it down, either. As it happens, the person with whom I lived at the time worked for the Episcopal Church (ECUSA), which is a part of the Anglican Communion, and which is headquartered in New York City. At the time — and I assume this is still going on today — the ECUSA was pouring plenty of cash into the Anglican churches in Africa, and Tutu, who back then was a frequent visitor to New York and very chummy with the ECUSA honchos and with Episcopal clergy in the city, was an especially favored object of the ECUSA’s largesse.

In any event, my cohabitant idolized Tutu as a champion of peace, reconciliation, brotherhood, and human rights in the aftermath of apartheid. He even met Tutu once or twice, and after those encounters he was walking on air. He quite simply adored the man.

Of course, Tutu wasn’t the only big name associated with the end of apartheid. There was Nelson Mandela, who headed up the African National Congress, spent years in prison, and ended up President of South Africa. And there was Mandela’s predecessor as president, F.W. DeKlerk, who worked with Mandela to dismantle apartheid and eventually shared the Nobel Peace Prize with him in 1993. But before they won their Nobels, Tutu won his, in 1984, with the Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee hailing his leading role in “the non-violent struggle for liberation” in his country, “a struggle in which black and white South Africans unite to bring their country out of conflict and crisis.” Tutu deserved the honor: this was a man who, respected by both black and white, was able to persuade South Africans of both races, through sheer nobility of spirit, to resist uncivilized impulses and take the high road.

In his Nobel Prize lecture, Tutu sounded a noble note:

Unless we work assiduously so that all of God’s children, our brothers and sisters, members of our one human family, all will enjoy basic human rights, the right to a fulfilled life, the right of movement, of work, the freedom to be fully human, with a humanity measured by nothing less than the humanity of Jesus Christ Himself, then we are on the road inexorably to self-destruction, we are not far from global suicide; and yet it could be so different.

When will we learn that human beings are of infinite value because they have been created in the image of God, and that it is a blasphemy to treat them as if they were less than this and to do so ultimately recoils on those who do this? In dehumanizing others, they are themselves dehumanized. Perhaps oppression dehumanizes the oppressor as much as, if not more than, the oppressed. They need each other to become truly free, to become human. We can be human only in fellowship, in community, in koinonia, in peace.

I hadn’t thought about Tutu for a long time, but he’s been on my mind lately because of the horrors that are currently underway in the Republic of South Africa. In March, that nation’s parliament voted overwhelmingly to confiscate farmland from whites without compensation. Mass appropriation of white-owned land by black marauders is already taking place on a wide scale. Families that helped build South Africa and that have tilled their acres for generations have now either had their property stolen already or are huddling in their boarded-up, fenced-in homes waiting for an armed mob to come take it from them. And the assailants aren’t stopping at mere thievery. They have committed acts of physical cruelty motivated purely by greed and race hatred.

But the mainstream media in the West, almost without exception, have chosen not to pay attention to this issue, because a story in which blacks are the bad guys and whites are the victims doesn’t fit their narrative. Tucker Carlson, to be sure, has done segments about the issue on his Fox News TV show. PJ Media has reported extensively on it. Lauren Southern and Katie Hopkins have both made documentaries that can be viewed on YouTube. But few Americans and Western Europeans, I suspect, are aware of what’s going on.

I’ve been around long enough to remember white South Africans who struggled bravely against apartheid. Because I’m a literary critic, the names of two writers leap immediately to mind: Mary Renault and Nadine Gordimer. Both fought the good fight, although in different ways. Gordimer mounted the barricades, traveled the world giving speeches, and hence grabbed the headlines; Renault, whose temperament was more that of a reformist than that of a revolutionary, stayed at home and worked tirelessly behind the scenes to achieve racial justice. They were just two of many who strove selflessly to transform a system from which they benefited. If they were still alive today, what would they make of this evil new war on whites?

And what, I wonder, does Tutu think?

Yes, it’s true that, since his golden days, he’s fallen from his pedestal. He’s compared Israel to apartheid South Africa. Repeatedly. Sometimes viciously. Indeed, as Alan Dershowitz noted some years ago, Tutu has demonstrated “a long history of ugly hatred toward the Jewish people, the Jewish religion and the Jewish state,” and “has minimized the suffering of those killed in the Holocaust … by asserting that ‘the gas chambers’ made for ‘a neater death’ than did Apartheid. In other words, the Palestinians, who in his view are the victims of ‘Israeli Apartheid,’ have suffered more than the victims of the Nazi Holocaust. … He has been far more vocal about Israel’s imperfections than about the genocides in Rwanda, Darfur and Cambodia.”

Tutu is, then, an anti-Semite. Still, in South Africa he commands moral authority that he could put to some use in defense of his country’s white farmers. Why hasn’t he?

One reason might be that he’s not as young as he once was. He retired from his post of archbishop in 1996. He’s now 87 years old. It would be easy to assume that he’s too feeble these days to make public pronouncements, or that he’s suffering from Alzheimer’s. Nope. In fact, although he was hospitalized briefly in September, Tutu has since been described as being “in good health,” and in recent weeks has been keeping an extremely active schedule.

On November 19, at a ceremony in Cape Town, he presented awards to some of the survivors of the February massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. On December 9, he attended a dinner commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which he headed up, and which, in the immediate wake of apartheid, brought to light longstanding human-rights abuses, gave perpetrators an opportunity to express remorse, and provided victims with reparation and rehabilitation. The very day after the commemorative dinner came the news that a ministry based in Jacksonville, Florida, had teamed up with Tutu “in an effort to fight world hunger.”

So he’s been a busy fellow. But what has he said or done about the war on white farmers? I’ve googled away, and scoured Lexis, and found nothing. Not a word. Have I missed something? Has he in fact urged South African politicians to change their minds, and begged marauders to stay their hands? I hope so. If I find out that, in fact, he still views all South Africans as “members of … one human family,” and that he has defended the right of white farmers to retain their own land, then I might consider taking that framed picture of him — which is now gathering dust under my bed — and putting it up on the wall somewhere.

On second thought, though, I think I’ll wait until he also drops the anti-Semitism.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member